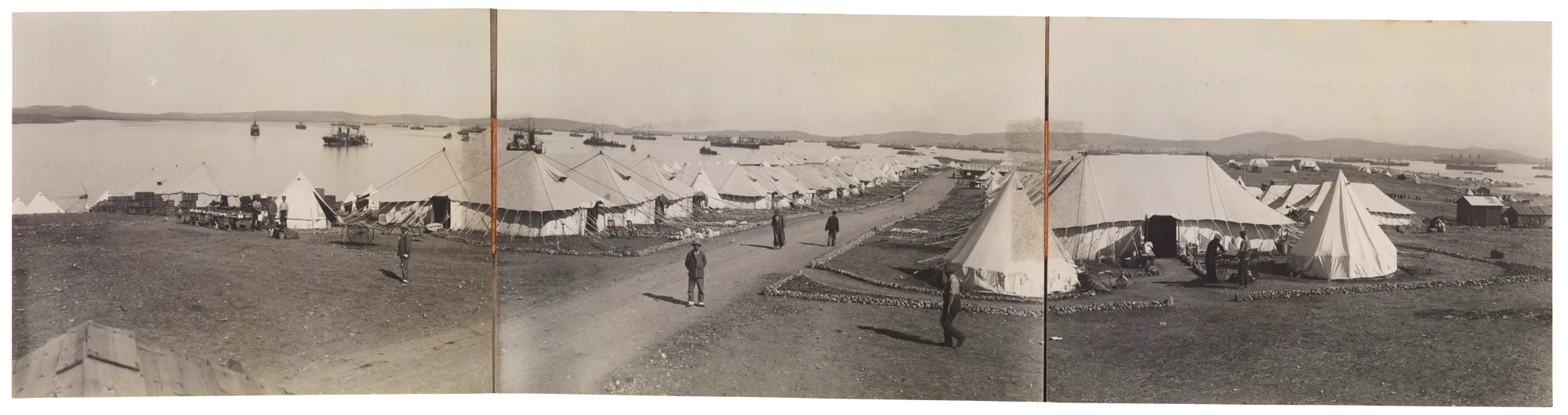

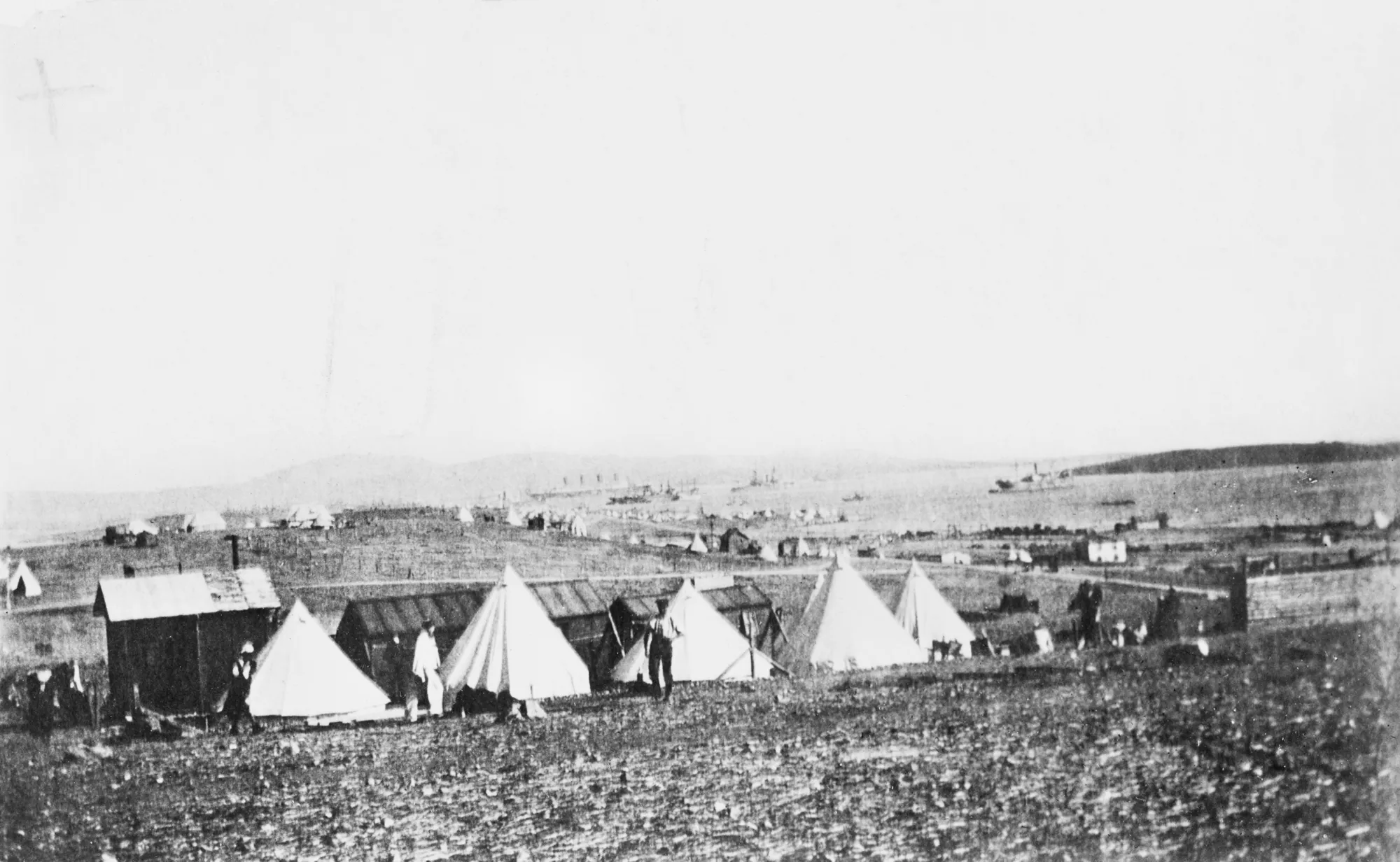

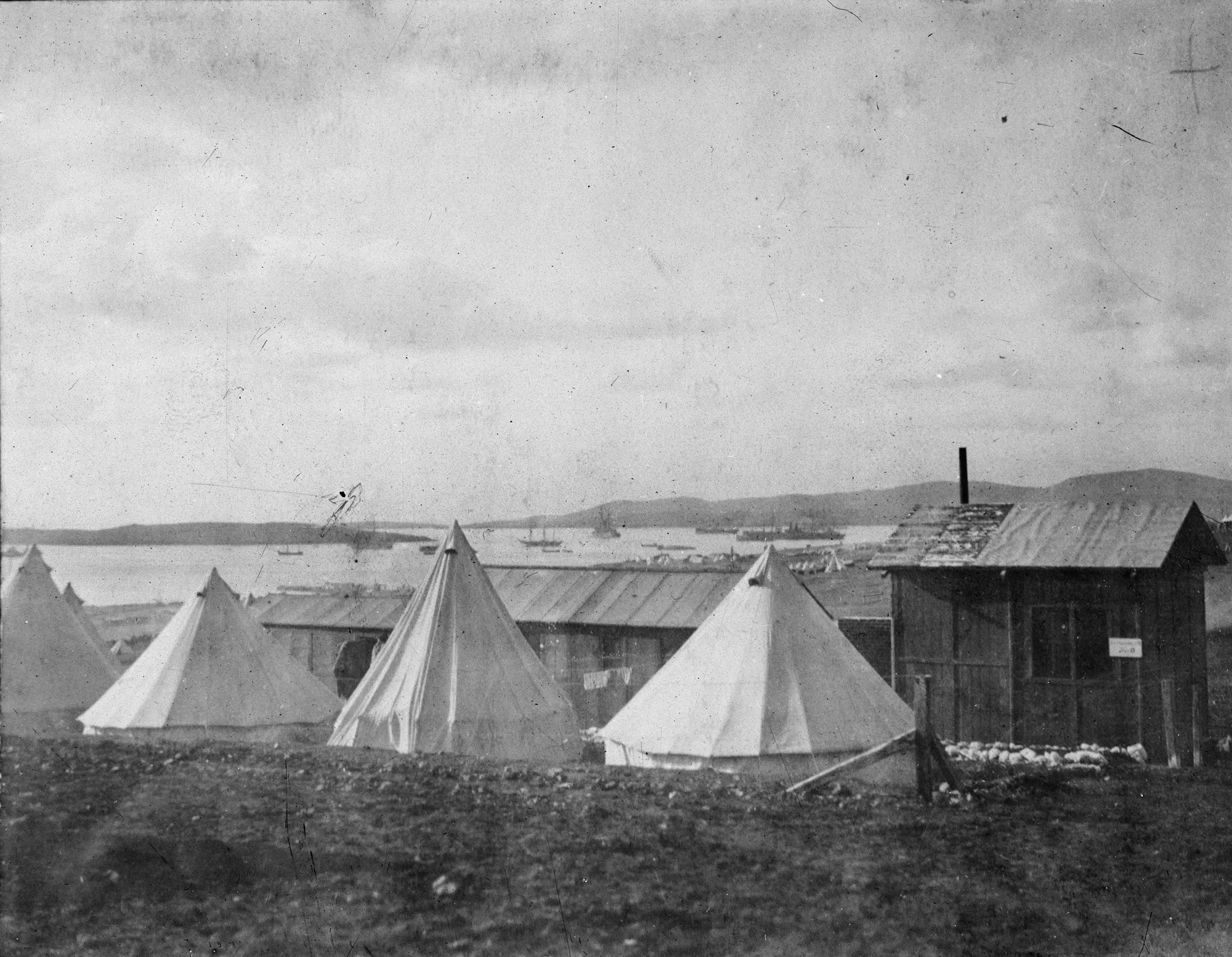

Lemnos was an important base for medical care and critical to the broader system of medical evacuations from Gallipoli during 1915 and the first weeks of 1916. Allied nations established several hospitals, including three Australian hospitals, intended for treating the ‘lightly wounded’. These men would be patched up and returned to the frontline.

Preliminary planning

Initially, medical planning for the campaign had been poor, as senior command expected a quick success. Casualty numbers increased through 1915. By the end of December, Lemnos’s hospitals could together treat more than 7,000 acute patients and 3,000 convalescents.

No. 1 Australian Stationary Hospital

In September–October 1914, Lieutenant Colonel H.W. Bryant formed No. 1 Australian Stationary Hospital (1ASH), comprising largely South Australians. It left Australia in December, with a staff of 96 that included no female nurses.

1ASH arrived on Lemnos from Egypt in March 1915. Its site was near the Australian camp, in East Mudros. The Red Cross had given Bryant £200 before 1ASH left Egypt to build up its essentials, such as drugs, instruments and X-ray materials.

It was the only hospital on Lemnos before the landings. On 9 April, the 3rd Brigade diary reported that 1ASH was treating some 200 ailing men. ‘Transport diseases’ were common among the troops, who were living in basic, close quarters.

In May, 1ASH received orders to move to Gallipoli as a field hospital. But within days the order was rescinded and it was re-established in East Mudros. It remained there until late October, when it was transferred to Gallipoli.

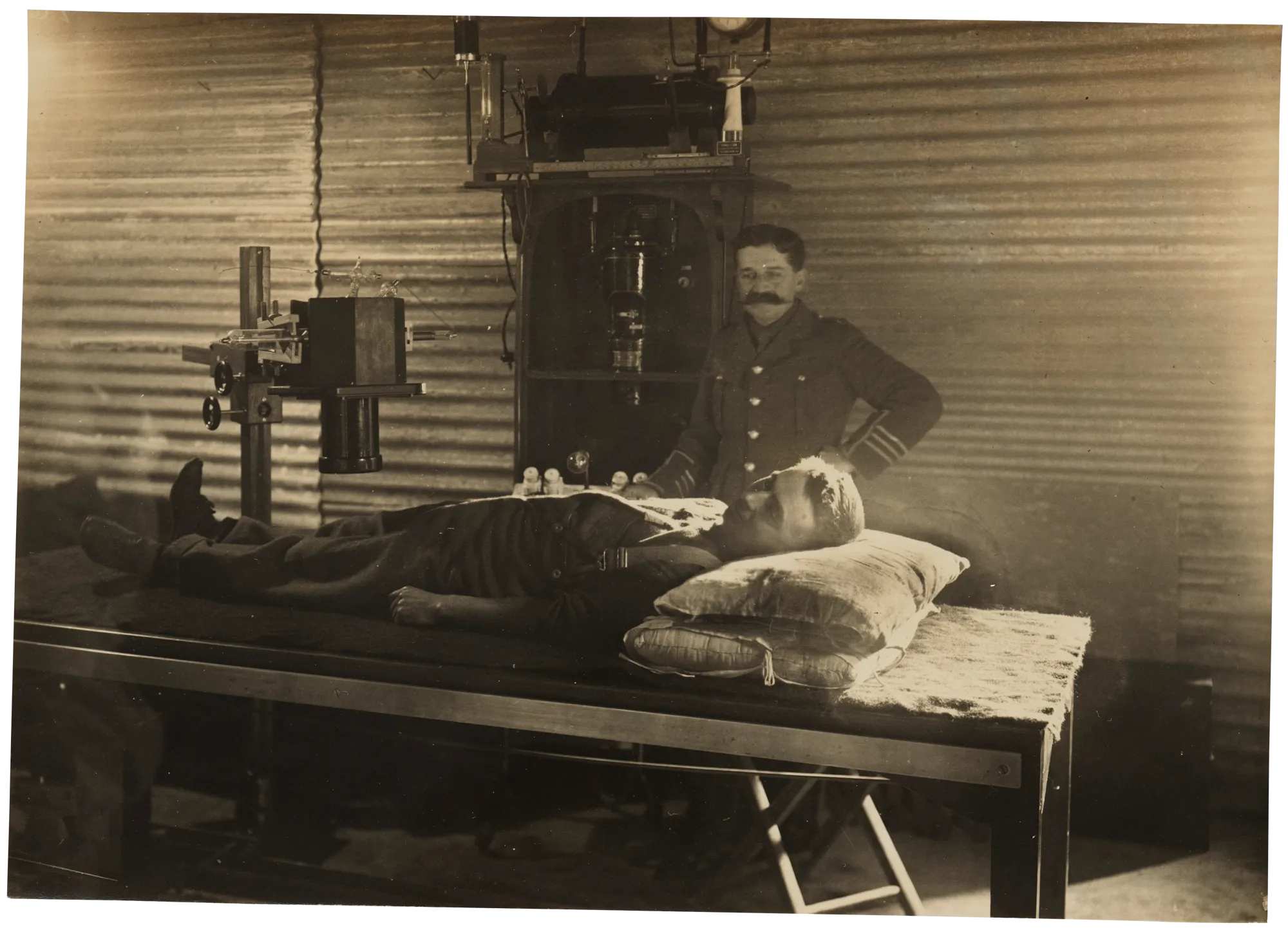

Electricity was used to illuminate the 1ASH operating theatre. Its busy X-ray unit serviced all other Allied hospitals on Lemnos until the establishment of 3AGH at West Mudros. It also had a telephone exchange, which it shared with other hospitals.

No. 2 Australian Stationary Hospital

Australia’s No. 2 Stationary Hospital (2ASH) arrived on Lemnos in June and was first set up in East Mudros, near 1ASH.

It was relocated in early August when the main medical precinct was set up in West Mudros. 2ASH comprised some 60 marquees, a separate block for infectious patients and a staff of around 140.

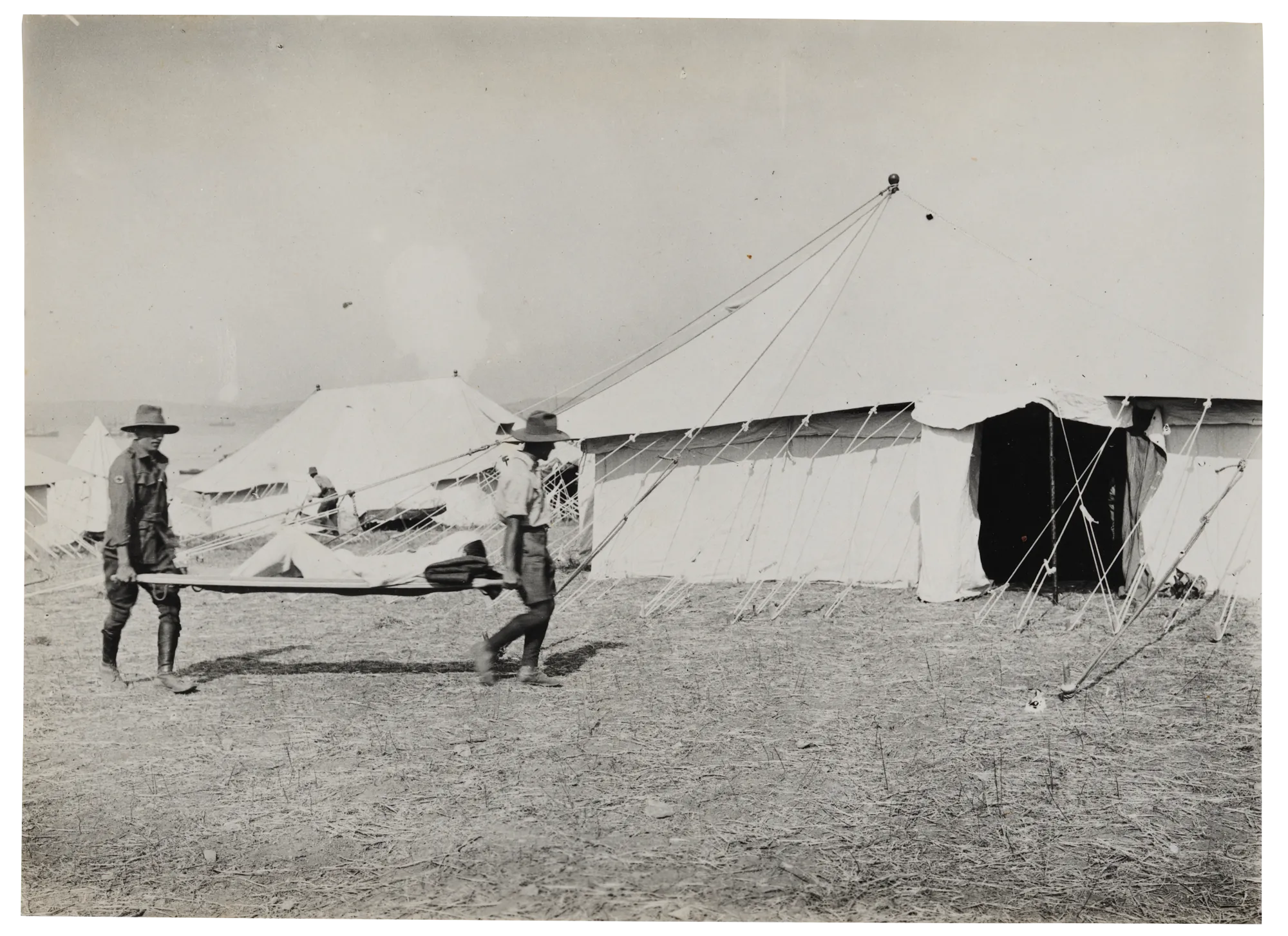

The sick and wounded were carried or wheeled on stretchers from the pier to the hospital as the ships arrived. The introduction of four motor ambulances at the end of September eased this task.

No. 3 Australian General Hospital

The military brass believed the August offensive would break the deadlock at Gallipoli. In readiness, No. 3 Australian General Hospital (3AGH) was established at Lemnos to treat wounded Anzacs.

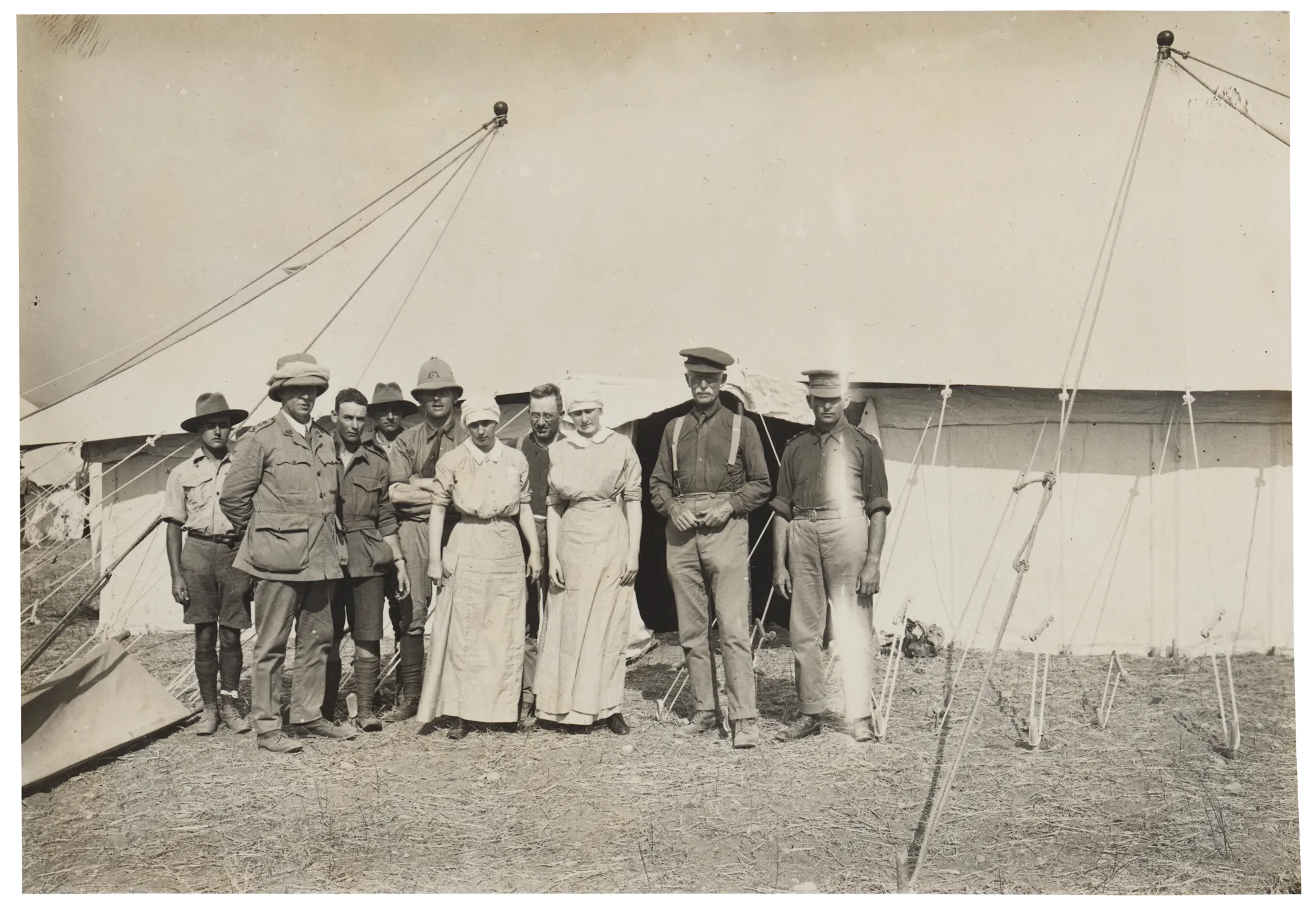

It would build on the capacity of 1ASH and 2ASH, and its medical team included (initially) 80 nurses. Among its staff were a solicitor, a pastry cook, farmers, carpenters, grocers, teachers and accountants. Some were medical students, others experienced wardsmen, dentists and chemists. Several claimed first-aid knowledge or nursing experience.

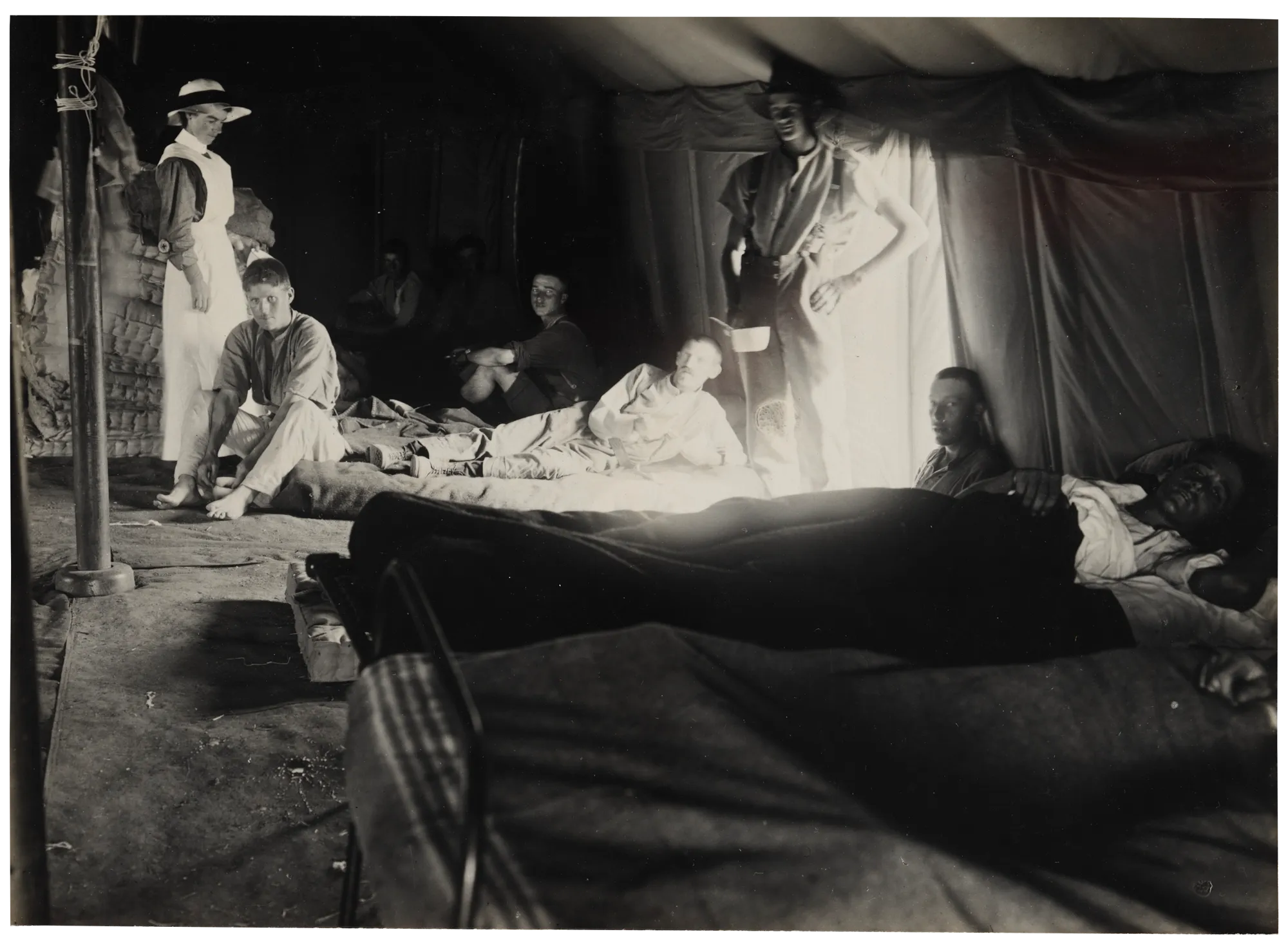

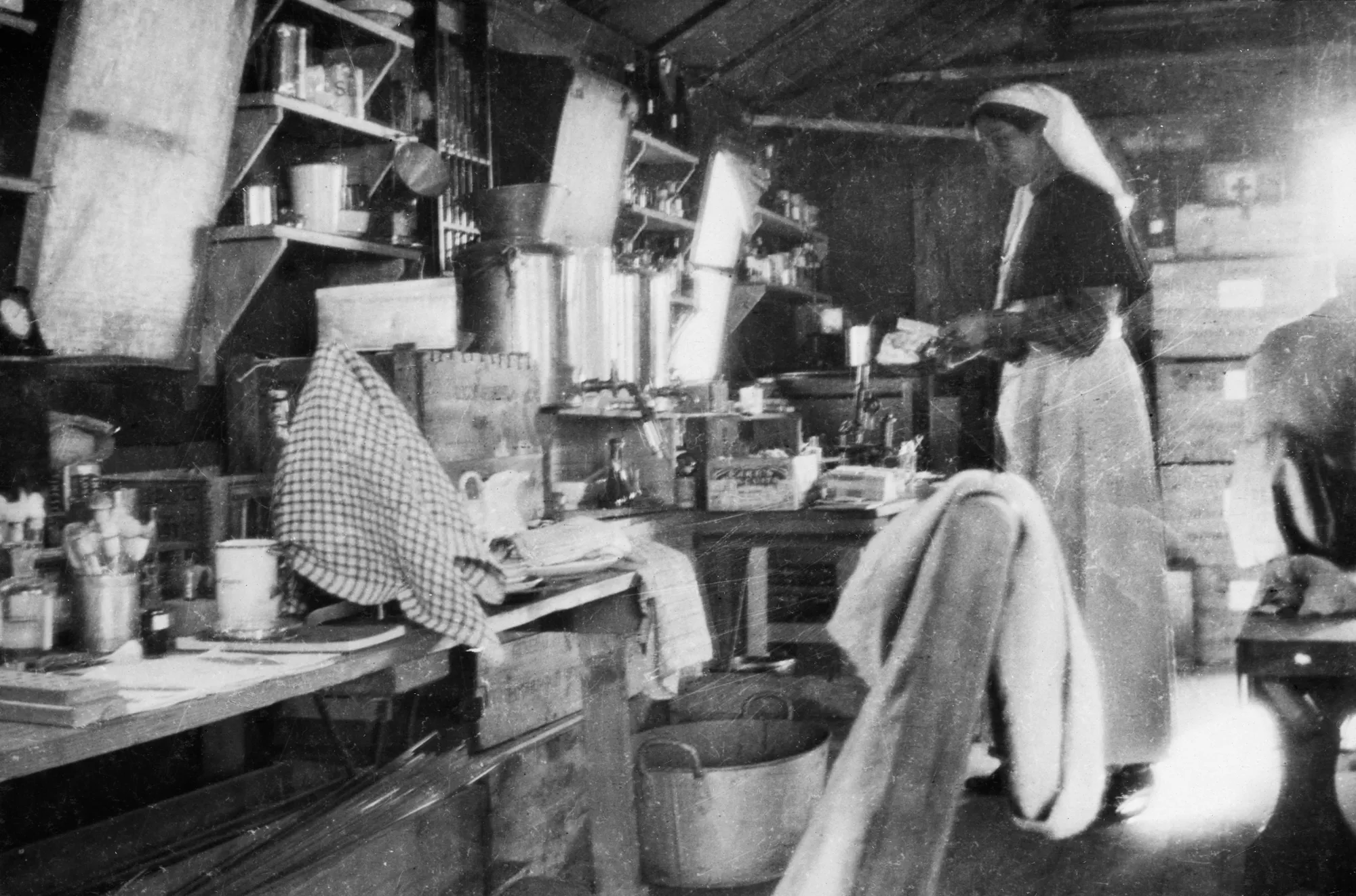

As 3AGH came ashore, so too did the waves of wounded. The challenges were overwhelming. There was little in the way of medical supplies, as the ship carrying them was delayed by weeks. Patient accommodation was barely existent and there was no supply of fresh water.

Staff did what they could with the little they had in those first weeks. But they soon established a well-run hospital.

Sydney surgeon Colonel Thomas Fiaschi was commander of 3AGH. Lieutenant Colonel James Dick was second in charge. Matron Grace Wilson was responsible for the hospital’s nursing staff.

‘Found 150 patients lying on the ground – no equipment whatever … had no water to drink or wash.’

Treatment

When 3AGH arrived on Lemnos, gunshot wounds were a chief cause of patient deaths. From later in August, sickness dominated.

The uncovered toilets, animal manure and unburied bodies at Gallipoli were ideal for flies to breed in their millions. They quickly spread contagious diseases such as dysentery and enteric fever (typhoid). This led to many evacuations for treatment, and some men died.

At 3AGH, paratyphoid A and B, jaundice and scurvy were all common. Dysentery was prevalent among both Gallipoli evacuees and Lemnos personnel. With little fresh water available for washing and the relentless flies, it was hard to avoid, even for hospital staff. They nicknamed the disease ‘Lemnositis’.

‘The laundry is one of our greatest difficulties here. We are allowed a gallon of water a head per day. It doesn’t go far when you do your own washing – so we study economy.’

– Staff Nurse Anne Donnell, letter, 9 Dec. 1915

PATHOLOGY

The pathology laboratory undertook ground-breaking research at 3AGH, drawing on the cases the hospital treated. Its research into typhoid-related diseases was especially fruitful. This led to a typhoid–paratyphoid mixed vaccine.

A member of the AANS, bacteriologist Staff Nurse Fannie E. Williams was part of the lab team. She was the only Australian woman to serve in this role during the First World War and was awarded the decoration of the Royal Red Cross in recognition of her valuable services with armies in the field.

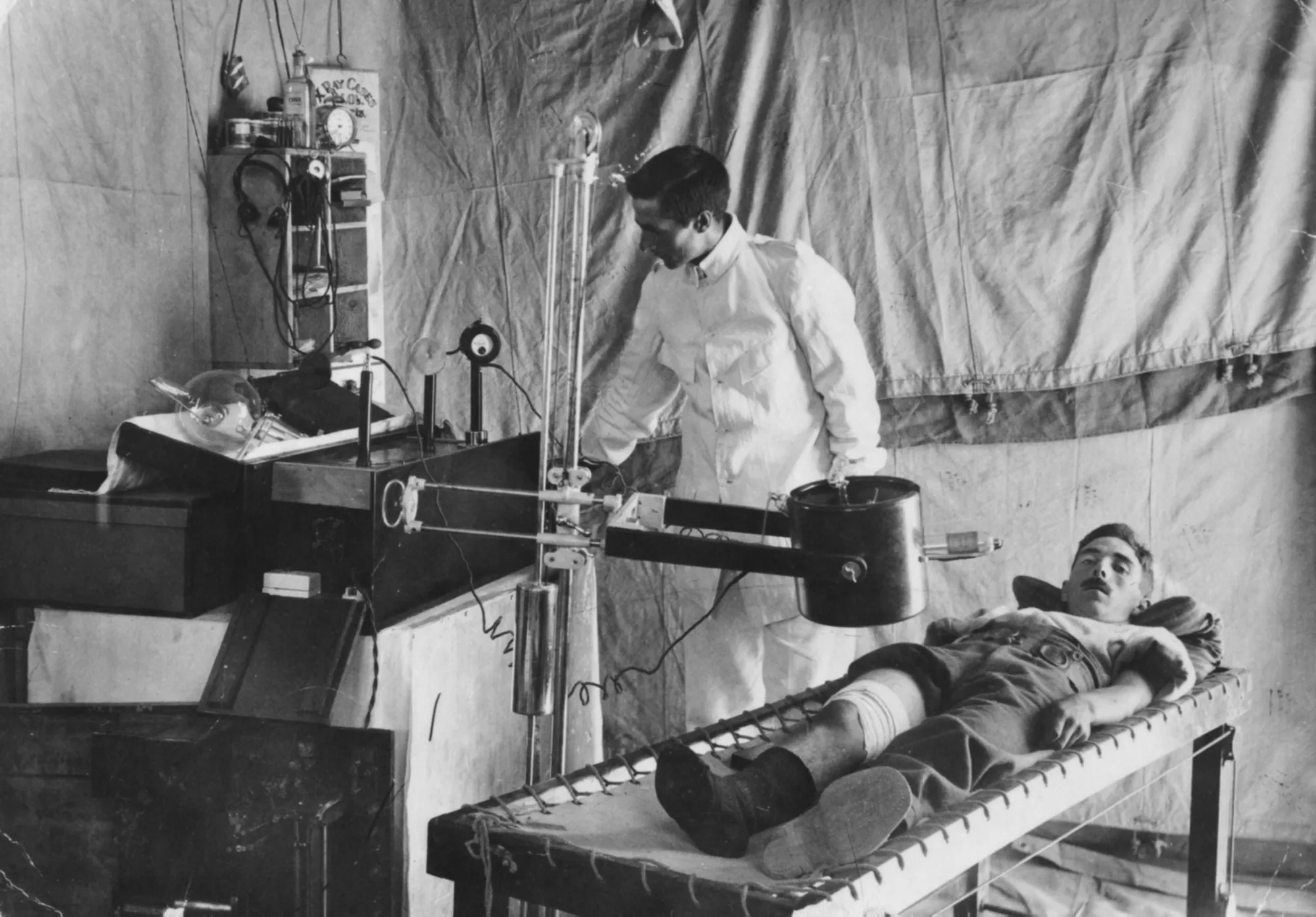

RADIOLOGY

X-ray technology had existed for just 20 years at the outbreak of the war.

Renowned radiologist Dr Lawrence Herschel Harris ran 3AGH’s X-ray facility. Initially, 1ASH was the only hospital on Lemnos to have an X-ray unit, so it was used for casualties being treated in other medical facilities.

Harris and his colleague Private Albert Savage were also keen photographers, and both visually documented life and conditions on Lemnos.

OPTHALMOLOGY

Eye health was essential for all personnel. Major John Lockhart Gibson led an ophthalmic clinic at 3AGH. It treated patients of all Allied hospitals on Lemnos. The clinic also treated other service personnel and members of the civilian population.

The clinic was first housed in a marquee at 3AGH, but moved to a purpose-built hut of around 7.3 x 3.5 metres. It was equipped with instruments purchased through funds from the Queensland division of the Australian Red Cross.

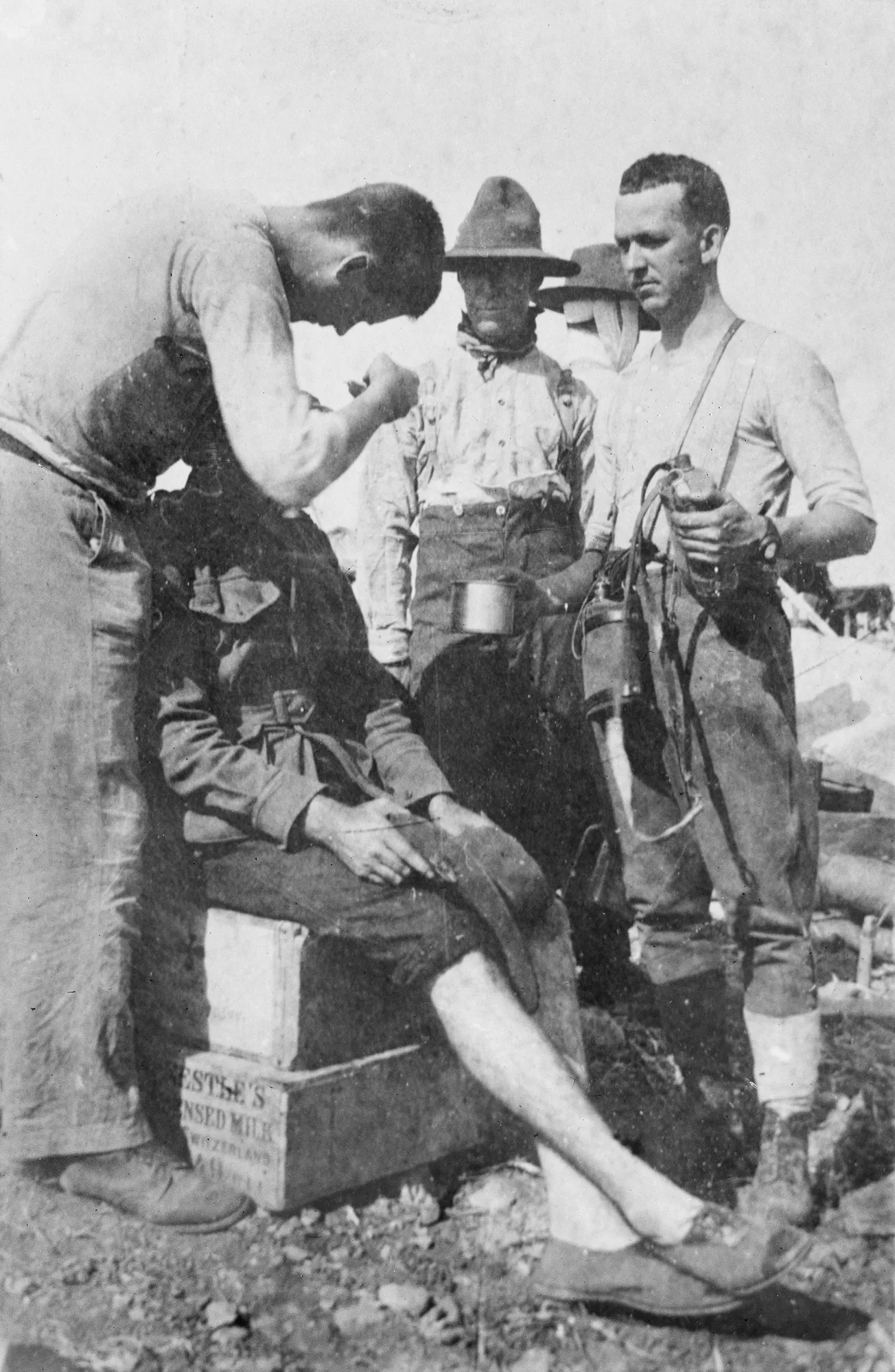

DENTISTRY

Although good dental health was compulsory at AIF recruitment, the need for dentistry services during the war was immense. This was partly due to the diet of troops, especially the damage done by the hard biscuits in soldier rations. In the first three months of the Gallipoli campaign, dental issues led to the evacuation of an estimated 600 men.

On Lemnos, dental services were provided at 1ASH before the landings took place. Hospital commander Colonel Bryant described this work as ‘invaluable to both the Navy and Army’.

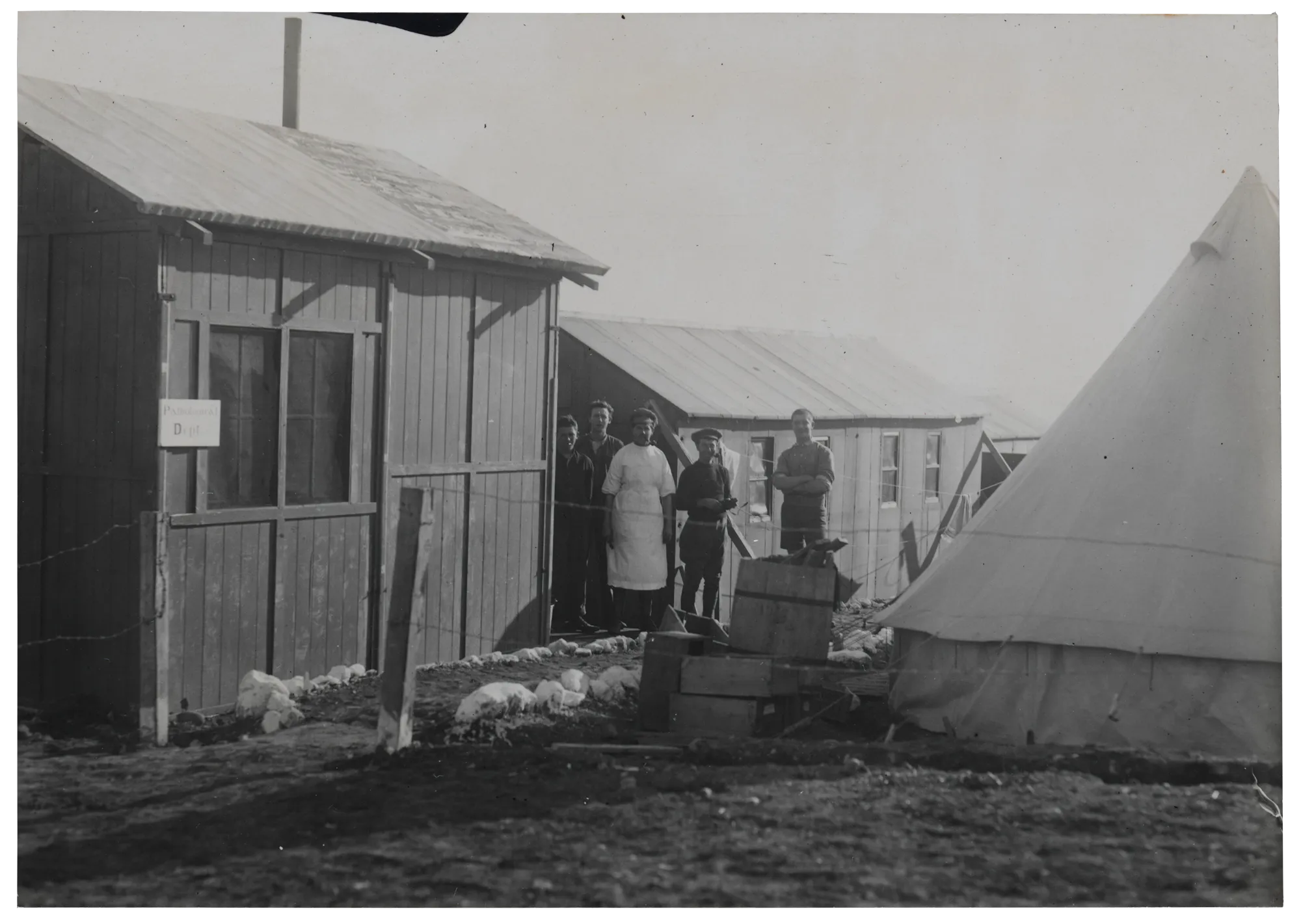

From August, the dental unit at 3AGH operated with two Australian dentists, one of whom was Lieutenant Frank Marshall. Its three surgeries were eventually housed in weatherboard huts. These had concrete floors and white calico windows to keep out the dust, rain and flies, and the Red Cross funded the equipment.

Between September and December, the dental unit treated around 1,380 military and naval personnel. It also treated men from the Egyptian, Greek and Maltese Labour Corps, as well as Turkish prisoners of war.

Tooth extractions were common. Other typical treatments included scalings, crowns and the repair and creation of dentures.

SHELL-SHOCK

For most troops, Gallipoli was their first exposure to the terror of warfare. Many suffered from shell-shock, or neurasthenia, what we’d now call PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder). Nurses, too, suffered from the awful strain of tending horrific wounds and witnessing bombardments.

‘The soldier was given a few days to “settle down” and then encouraged to whisper so normal speech would return, but it was noted that progress was compromised if the soldier experienced another shock during his recovery. The introduction of “Corps Rest Stations” [such as Sarpi Rest Camp] gave the frontline soldier a chance to recover from the bombardment of battle and reduce the likelihood of symptoms becoming chronic.’

– Ruth Rae (historian), Veiled Lives, p. 177

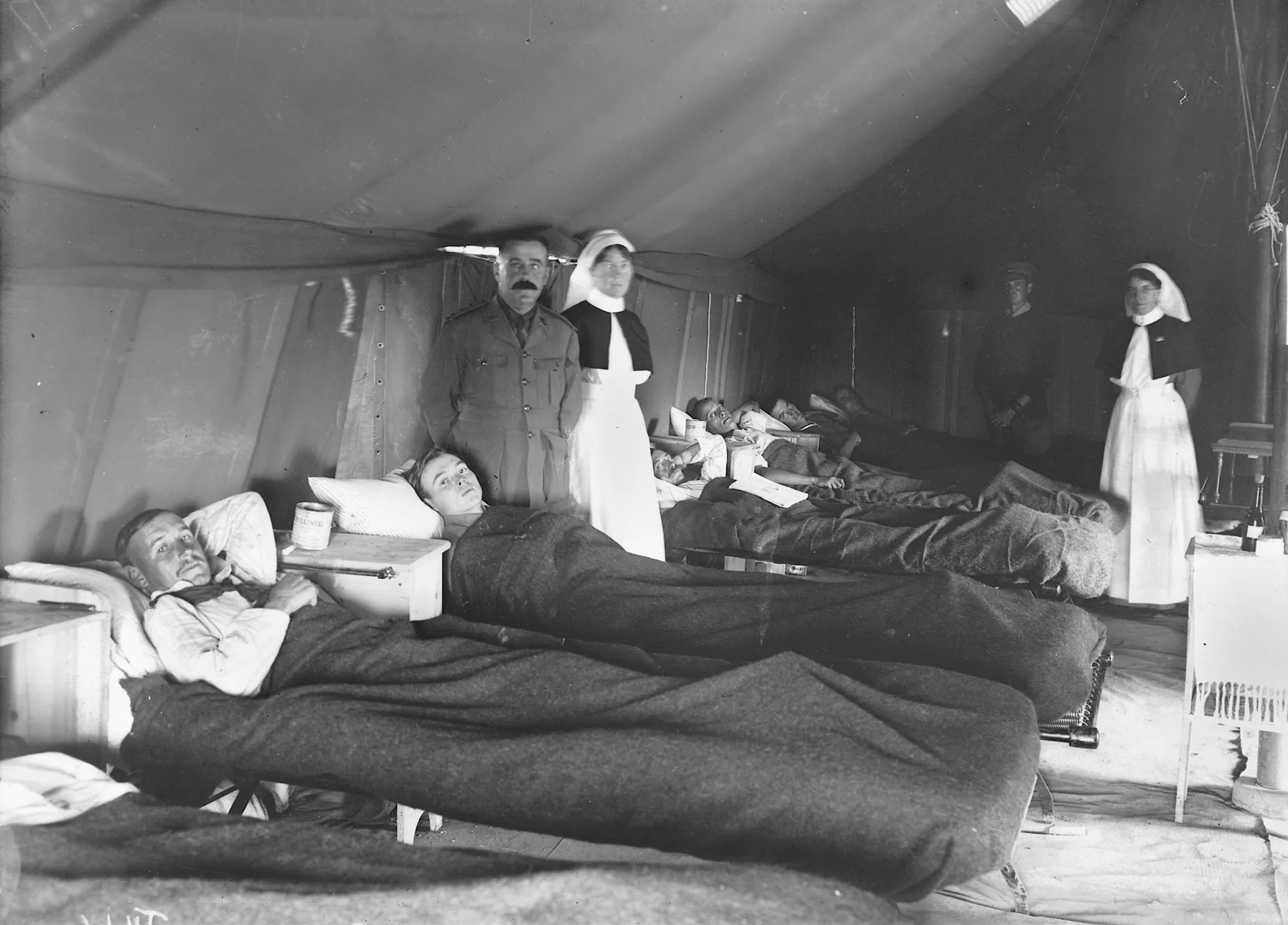

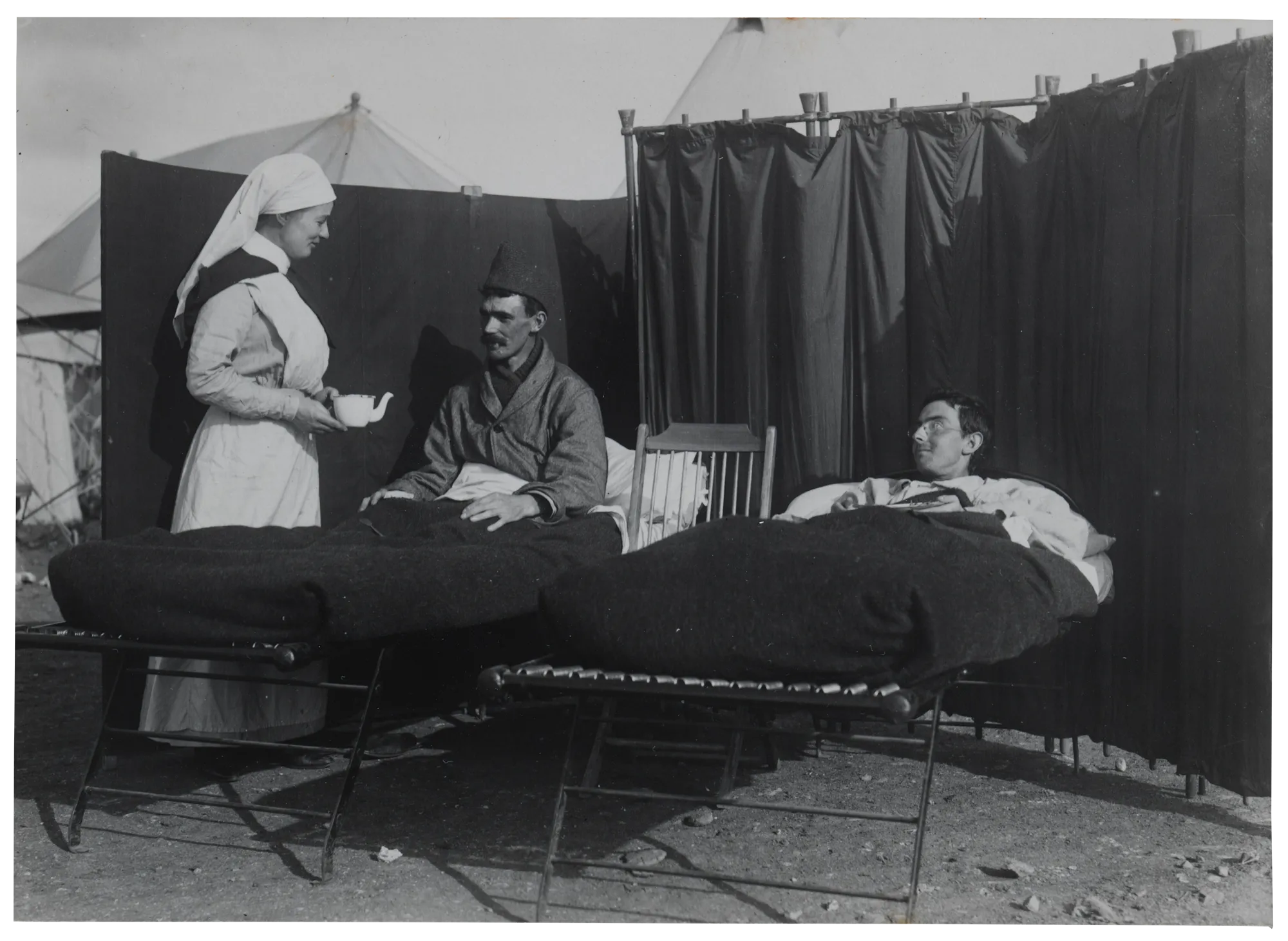

Australian Army Nursing Service

Around 2,860 nurses from the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) served during the First World War, some 130 serving on Lemnos. They tended the sick and wounded at 3AGH and 2ASH between August 1915 and January 1916.

Conditions were rudimentary. Initially, the nurses slept on the ground without mattresses. Their uniforms were not suited to the hot summer, but the women froze in winter. Eventually, the appalling conditions led to an investigation of 3AGH’s Colonel Fiaschi. Major General Fetherston concluded Fiaschi ‘treated Nurses shamefully – No consideration whatever … I believe the Hospital would have collapsed but for the Nurses’.

The nurses’ resourcefulness and compassion were invaluable, especially on their arrival. From day one of the campaign, Australian nurses also served on hospital ships. In each of these medical settings, nurses’ care extended to social and emotional support.

‘The wounded men were being brought in motor ambulances from a mine sweeper & put at my feet. I could weep hysterically now it is over. I got them in the shade & rushed to my tent for my cup & pillow & two sheets a sister had given me out of her 6 she had brought with her – & got them tea from our billy tea & tried to keep the flies from their wounds.’

– Sister Betha McMillan, letter, 23 Aug. 1915

Medical evacuation

Thousands of sick and wounded passed through Mudros Harbour each week. The most serious cases received treatment in advanced medical facilities farther from the frontline.

Hospital ships were key to evacuations, transporting critical cases to Egypt, Malta, England and sometimes Gibraltar. Facilities and treatments at these places were superior to what Lemnos could offer. During the week of 14–20 October, for example, 5708 cases were treated on Lemnos and 7,740 transferred: 2,595 to Egypt, 1,290 to Malta and 3,855 to England.

The ships on which Australian nurses primarily served were the Gascon and Clan MacGillvaray. The staff of Gascon also comprised medical officers from the Indian Medical Service, a Royal Army Medical Corps matron and orderlies from the Royal Army Corps and the Indian Medical Service.

The standard of hospital ships varied greatly. Some were hastily converted transports. The medical staff of each included around six doctors and 10 nurses, supported by 40 orderlies.

Staff would have been working in often-terrifying conditions.

‘We are in Mudros with 954 patients, they are all over the decks, they are a great many sick boys lying about on deck.’

– Sister Ella Tucker (hospital ship Gascon), quoted in Guns and Brooches, p. 44

‘Shells are bursting all around. We are off Gaba Tepe.’

‘We took 700 on board, and when you think they all had to be fed, the 400 cot cases washed, and all those dressings done, fractures set, serious cases operated on, and every man’s name and regimental details entered up in the 24 hours.’

Conditions on Lemnos

The weather affected the sick, the wounded and the able-bodied alike.

During the arid summer flies were at plague proportion. They made daytime sleep difficult for convalescing patients. Come summer’s end, plummeting temperatures, storms and heavy rains replaced the heat.

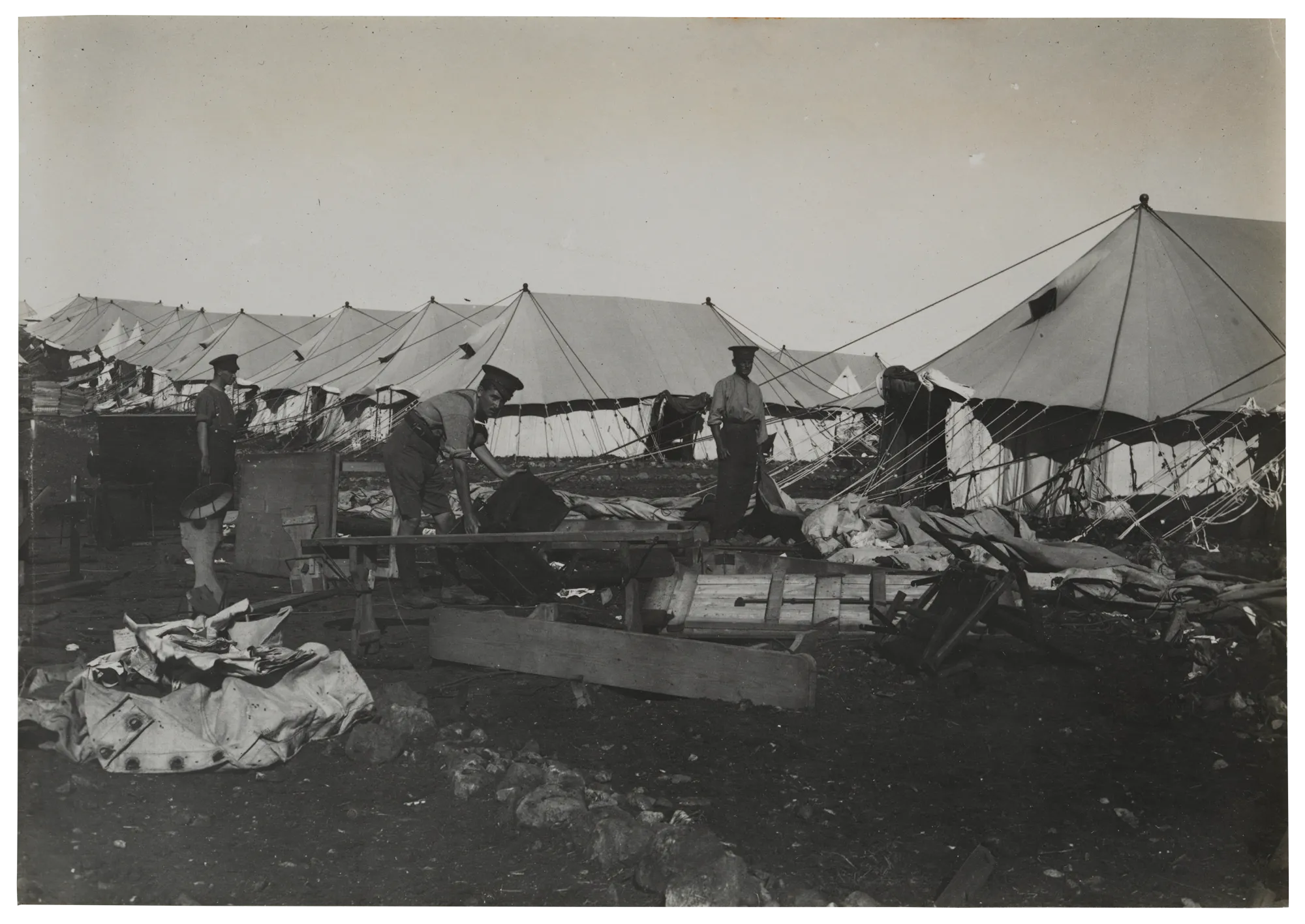

Flooding rains would drench mattresses and the fierce winds were a particular problem. Hospital tents would collapse or tear in Lemnos’s gales, forcing staff to quickly re-erect them before tending their patients. ‘I don’t think I shall ever get over my dread of wind’, wrote Staff Nurse Louise Estelle Young, ‘night after night, every bit of canvas creaking, shaking & straining & your mind always wondering which would collapse next’.

Living conditions were primitive for all.

‘We felt the blizzard ourselves and we don’t know how we endured it, because we have no proper shelter. We still work in tents and have to run out into the cold and bleak wind all the time. We were nearly all crippled with chilblains, but it was nothing to the state of the boys.’

– Staff Nurse Emily B. Taylor, The Maitland Daily Mercury, 12 Feb. 1916

Exiting Gallipoli, leaving Lemnos

Hospitals on Lemnos increased their capacity before the evacuation of Gallipoli, as many casualties were anticipated. Men recovering at Lemnos were sent to Egypt to free up beds.

Yet there were few causalities, so in late December, the hospitals reduced their capacity.

The exhausted evacuees recuperated at Sarpi and other camps, and sick or wounded Anzacs received care at 3AGH and 2ASH. The 1st Field Ambulance also served temporarily as a stationary hospital at Sarpi Rest Camp.

In early January 1916, 3AGH and 2ASH began emptying their wards, packing and preparing to leave Lemnos. The two hospitals left later that month, sailing the two days south-west across the Mediterranean to Egypt.