Lemnos was a strategic location for the Allies, which they used as an advanced medical and supply base during the Dardanelles campaign. It was less than 100 kilometres from the Gallipoli peninsula, and its sweeping natural harbour could provide anchorage for a great many ships.

East Mudros

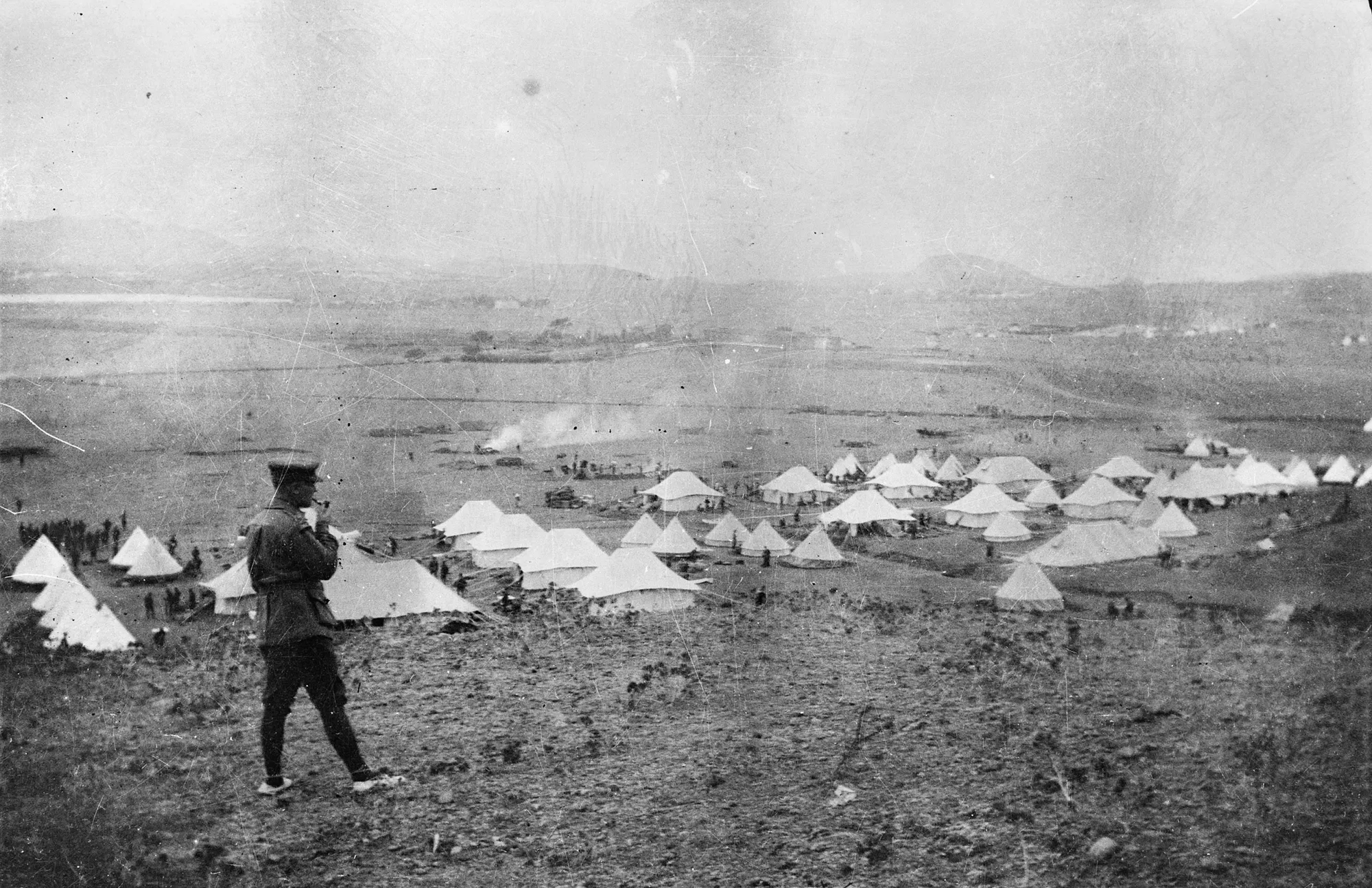

Australians first set up camp on the eastern side of Mudros Harbour, near the French and British camps.

The 3rd Brigade selected a site on a small hill overlooking the harbour, to the north of Mudros town. There, they laid out the Australian camp and helped erect No. 1 Australian Stationary Hospital (1ASH) nearby.

These first Australian arrivals scoured the island for freshwater sources. Because water was scarce, only around 1,000 men stayed at the camp, the rest on their ships. Over the following weeks, the troops sunk wells. In April, supply ships also brought fresh water from Alexandria to help address the shortage.

Most Anzacs arrived over 7–17 April and stayed on their troopships in Mudros Harbour due to the freshwater problem. They went ashore on cutters, lighters and other small watercraft to train for the coming battle and to help establish facilities.

Preparations

From March 1915, the Allies transformed Lemnos into a military base. Senior officers planned the landings and assault on the Gallipoli peninsula, while soldiers trained for fighting. The troops were accommodated on the island and onboard ships in the harbour. Senior officers stayed on the island of Imbros.

On 4 March, the Australian 3rd Brigade and a contingent of other units arrived in Mudros Harbour. The 3rd Brigade would train as the covering force for the landing at Ari Burnu, just north of Anzac Cove.

As other Anzac troops arrived through April, they prepared for battle and trained for the difficult coastal landings. They practised lowering and raising row boats from the transport ships. They disembarked and re-embarked on rope ladders, dressed in full kit and with heavy packs. Their punishing training involved long route marches and rocky hill climbs. They practised battle formations and mock attacks.

The troops also helped establish the essential infrastructure to support the campaign. They were kept busy building roads, depots, piers and the like.

‘Today the whole Brigade landed on Lemnos as a test landing. It was a long and tedious process. Some landed in Ships Boats. A slow but sure way. In our case a Naval Mine Trawler came alongside and about 500 men in heavy marching order (just as they will land on the Dardanelles coast) went down the side on rope ladders & were taken close in shore where we transhipped in boats & cleared for the beach. After landing we marched about a mile inland and camped for dinner.’

– Private Richard Henry Chase, diary, 15 Apr. 1915

Security and submarines

Lemnos was a key shipping and supply base, so security was crucial. Its location and the failed February assault on the Dardanelles made it an attractive target.

To aid security, in March the Allies built an anti-submarine boom across Mudros Bay. It separated the inner and outer harbours at the bay’s narrowest point.

The boom comprised about 6.5 kilometres of submerged cables, mines and nets. It stretched between Turks Head (now Pounda) Peninsula and Meganoros Point. Guns were mounted on the shore at each end and warships patrolled the boom.

‘An Austrian submarine was caught in the nets near the entrance of the Harbour, the crew are prisoners on the island.’

– Staff Nurse Lucy Daw

To enter the harbour, pilot boats guided Allied vessels through an opening measuring around 45 metres. It closed at sundown, so vessels arriving any later dropped anchor for the night in the outer harbour.

Sangrada Point lighthouse was on the eastern side of the entrance to the inner harbour. On 10 March, it temporarily extinguished its light. But this security tactic was not without risk. That night, the Australian submarine AE2 ran aground when it entered the inner harbour. Following repairs to its hull, AE2 went on to play a crucial role during the Gallipoli landings.

AE2 was one of Australia’s first two commissioned submarines. It departed Australia for the Mediterranean on 31 December 1914, with the second convoy.

British Lieutenant Commander Dacre Stoker captained AE2. Its first task was to patrol the entrance to the Dardanelles strait during the February naval campaign. AE2 then came to Lemnos to prepare for the April landings.

On 25 April, AE2 navigated the marine minefield and fortified entrance to the strait. Allied command directed Stoker to ‘run amok’ in the Sea of Marmara. The aim was to disrupt enemy forces and their ability to resupply troops.

After five days’ chase, torpedo-boat fire damaged the sub. This caused mechanical failures and forced AE2 to surface. Stoker ordered the sub’s scuttling. No lives were lost, but the submariners were held prisoner for the war’s duration. Four of the crew perished in captivity.

The Gallipoli landings

The Allied armada departed Mudros Harbour early on 25 April. A voyage of four or so hours lay ahead.

Landing at Gallipoli peninsula was complex. Troops were first transferred from their transport ships to British destroyers. Once they were near the landing sites, they boarded the destroyers’ rowboats. Armed steamers towed the rowboats to around 100 metres from the shore, and from there the troops rowed.

On that first day, some 16,000 Australians and New Zealanders went ashore on the narrow beach near Ari Burnu. The British and French troops were to their south. The Anzacs were met by the gunfire of an enemy dug deep into the steep, ridged slopes overlooking the beach. Around 2,000 Anzacs were killed or wounded that day.

The ambitious plan to take the peninsula was failing from its start. General Sir Ian Hamilton denied an early request to evacuate troops: ‘You have got yourself through the difficult business, now you only have to dig, dig, dig until you are safe’. Little gain was made from the months of close trench combat that followed.

By the end of the campaign, Australia had suffered more than 26,000 wounded and ill, and 8,000 deaths.

Sarpi Rest Camp

Fighting continued through the long summer. It weakened and wearied the men and achieved little. British commander General Sir Ian Hamilton ordered an August offensive at Gallipoli. The goal was to take territory in the northern sector of the Anzac position and break out of the beachhead in which they had been besieged since the landing. This was a failure that cost many lives.

Gallipoli’s geography allowed for no rear base to which soldiers could withdraw to rest. It was clear in the wake of the August offensive that men from the early landings needed to recuperate.

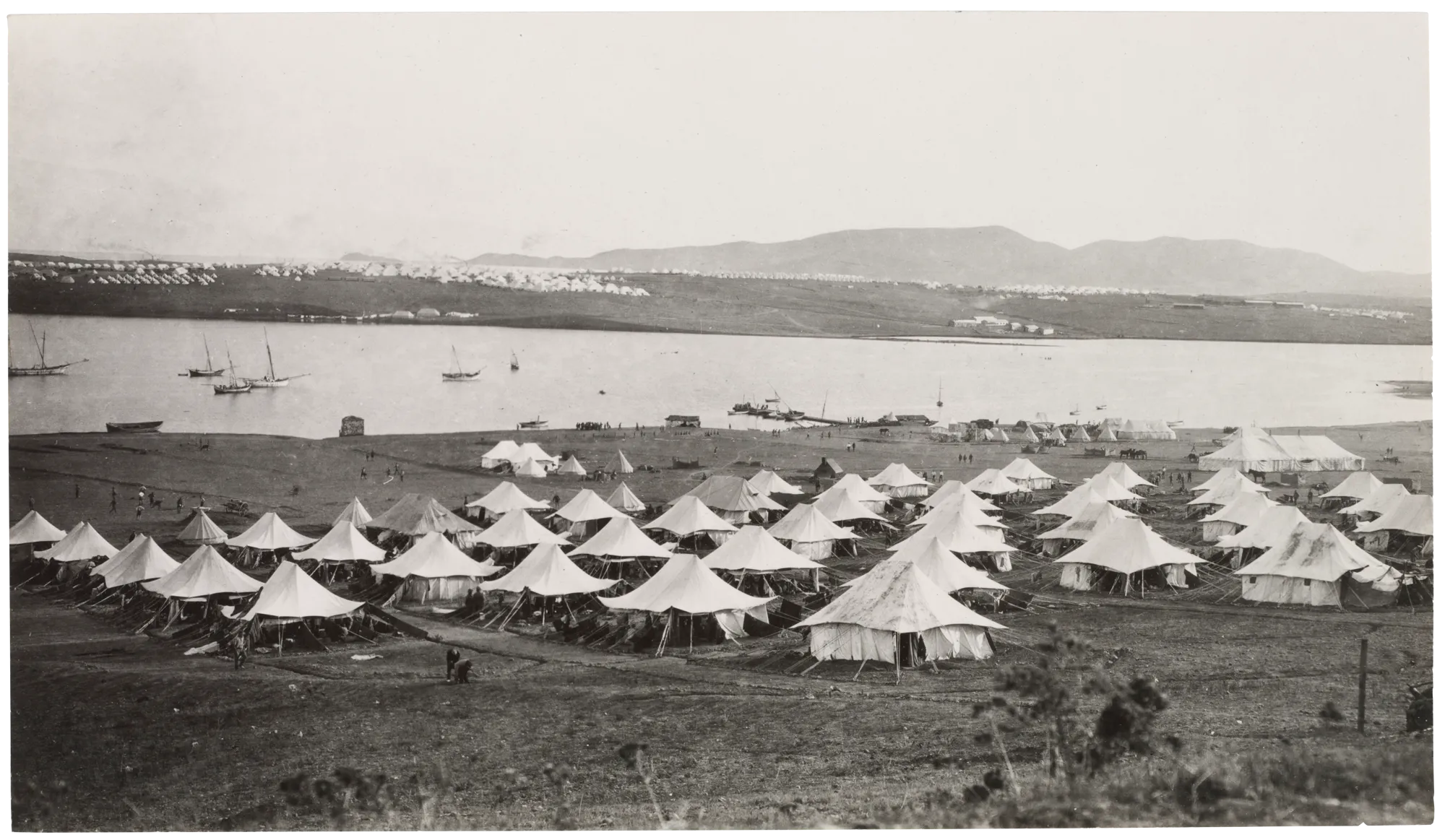

Sarpi Rest Camp was established on Lemnos for this purpose. Battle-weary Australian troops soon began arriving. Some reinforcements from Egypt also camped at Sarpi on their way to the front. Service units such as bakers and butchers were stationed at the camp.

Camp commander Colonel John Monash was frustrated by a shortage of tents and shelter. But for many Anzacs, Sarpi would have provided some comfort.

Sarpi was not a place to be idle. As men regained their strength, they engaged in an increasing number of military exercises. This included route marches, bayonet fighting, fire control and compass reading. They also undertook guard duties and moved stores between piers and depots.

‘Here at least there was no shelling, and the food, in quality and quantity, surpassed our most sanguine expectations. For the first time on active service we tasted the luxury of [army] canteens ... Day by day the men gained strength until they were colourable [sic] imitations of the original arrivals at Anzac.’

– Major Fred Waite, The New Zealanders at Gallipoli, n.p.

![Dead tired with shoes and sox [socks] slung over their shoulders](/sites/default/files/styles/compress/public/2025-01/DVA%20ID67b%20SLNSW_FL1524029.png.webp)

Evacuation of Gallipoli

After the August offensive, Allied command believed success at Gallipoli was impossible. General Sir Charles Monro recommended withdrawal.

The withdrawal was carefully planned. Several clever tactics gave the impression Allies were preparing to defend their position through the winter, not evacuating. Most of the troops were evacuated over three weeks in December. On 20 December, the last of the Anzacs left Gallipoli. British and French troops completed their evacuation from Helles on 8 January 1916.

Some troops had departed Gallipoli before the evacuation. The Australian 3rd Brigade, for instance, arrived at Sarpi Rest Camp in late November. The evacuated Australians recuperated at Sarpi and at camps on the eastern side of the bay.

Around 50,000 Allied troops arrived on Lemnos in December. Some 14,000 went to Imbros, the Greek island around 25 kilometres west of the Gallipoli peninsula.

Many soldiers arrived in need of medical attention. One Private Roy Kyle recalled seeing ‘literally hundreds of men collapsed ... men lying on the ground tended by medical orderlies.’