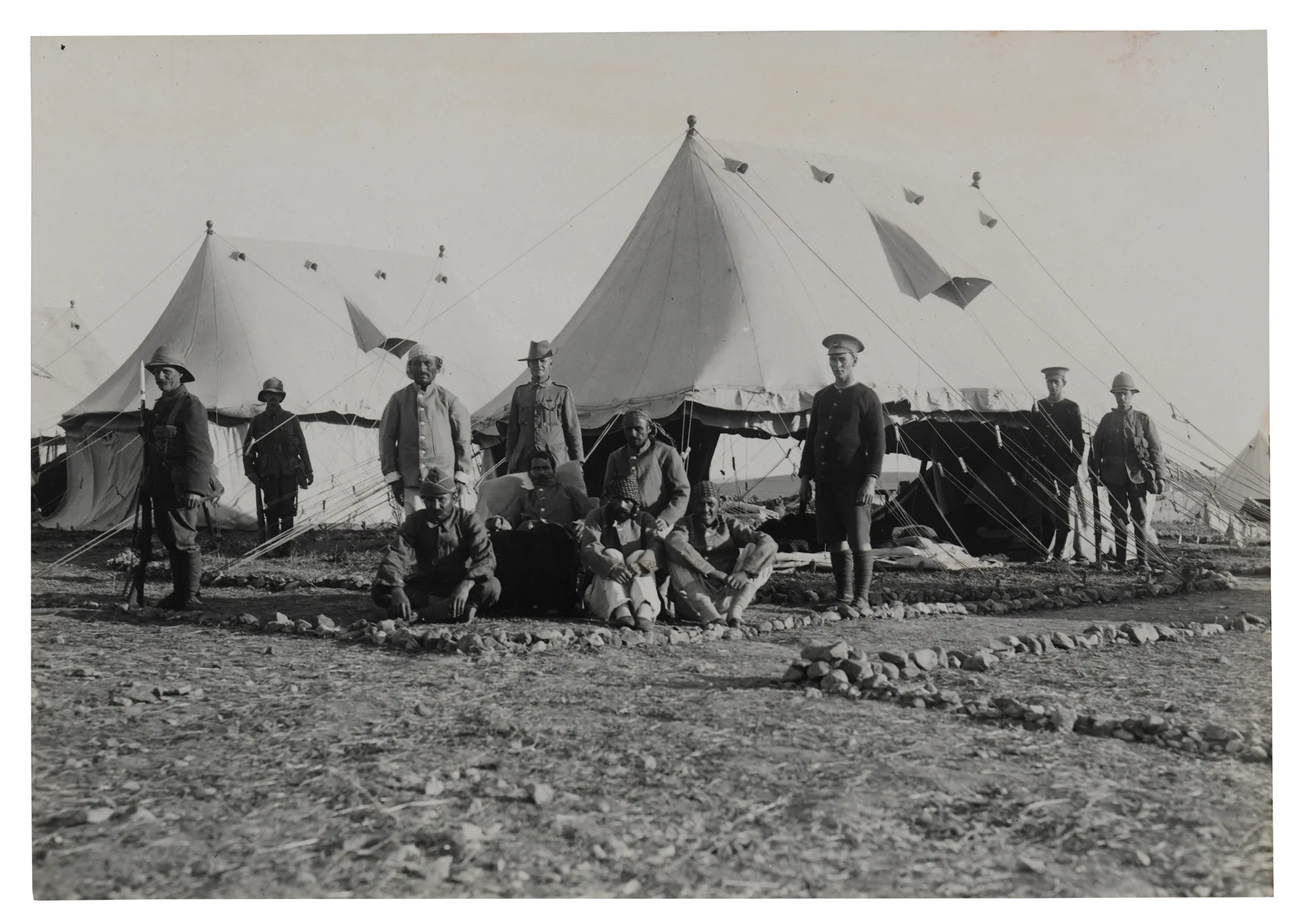

During the nine months that Australians were stationed on Lemnos, they met and worked with people from many countries and cultures.

They explored the island and formed ties that would help sustain them through the difficult conditions of serving at Gallipoli and on the Aegean island.

A multi-nation hub

‘The place is full of French regiments, Zouaves, Senegalise, Algerians etc, besides Hindoos, Soudanese, Australians, British, then Greeks who have enlisted in the French also New Zealanders. Add to these a sprinkling of nomads of other races & a good mixture is made.’

– Private Harry Gissing, diary entry, 27 May 1915

Lemnos brimmed with people from many countries. Staff from one nation would sometimes assist another. For example, Canadian nurses briefly worked at No. 2 Australian Stationary Hospital (2ASH). Sister Olive Haynes commented that they were ‘awfully nice – five of them here’.

Australian hospitals cared for casualties of other nations. This included Turkish prisoners of war, who were in two separate hospital compounds, and Greek civilians.

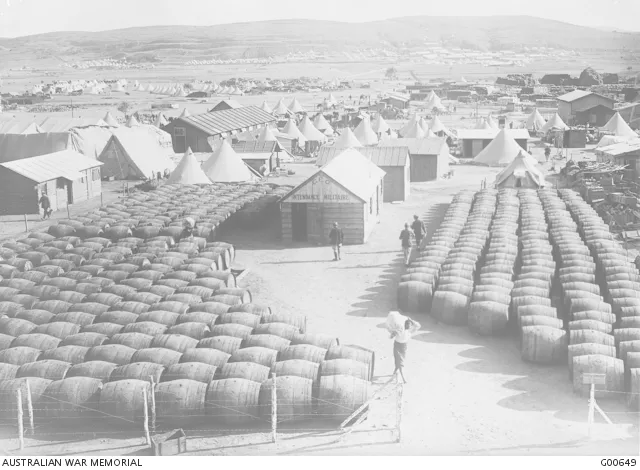

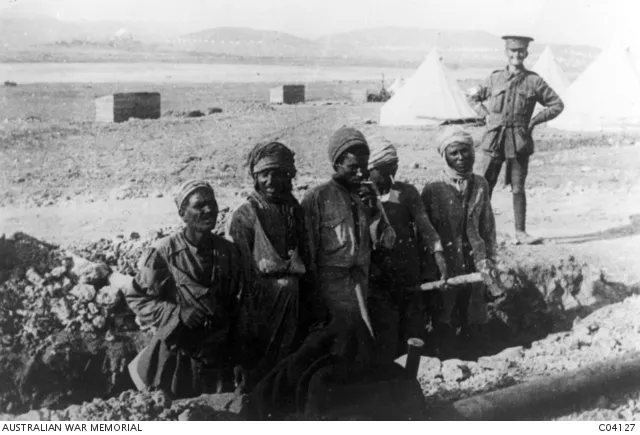

Greek and Egyptian labourers were part of the diverse cultural landscape. Many of the Greek Labour Corps came from Lemnos or nearby Lesvos and Tenedos. Recruited on six-month contracts, they helped establish the base. They cleared ground, made roads and constructed huts and hospital buildings. An estimated 2,000 also laboured on Gallipoli.

The Egyptian Labour Corps comprised many thousands of men, recruited by Britain as labourers. Around 3,000 served on Lemnos and Imbros and, from July 1915, at Helles and Suvla Bay. They built roads, carried supplies from piers to depots and cleared ground for huts and camps.

Friendship and support

Troops and personnel laboured long and hard, but they also found time for social activities. They sought passes to visit villages, held concerts and enjoyed social events at other camps. Rugby and cricket were popular among recovering soldiers, and New Zealand walloped Australia in one rugby game, winning 43–0.

During their limited free time, nurses would visit the men at Sarpi Rest Camp. They shared meals and sometimes participated in activities, including sports.

When their ships were at anchor in Mudros Harbour, Royal Navy crew and officers would often help the Australians. Delighted by his visit to HMS Vengeance, Private Harry Gissing happily received a parcel of meat and bread from the crew. ‘Nothing is too much trouble for them’, he wrote in his diary.

‘The ship herself is wonderful. Electric Elevators etc & the fittings are splendid. From here we went off to HMS Vengeance & asked permission to go aboard. A young fellow showed us round & everywhere we went they treated us splendidly shewing us the Guns, mechanism, shells, magazines etc. Then nothing would please them until we stayed to tea. They cooked us eggs & feasted us splendidly. Many of them had been working with our chaps on shore taking off the wounded & they could not do enough for us.’

– Private Harry Gissing, diary, 30 May 1915

Hospital staff routinely tended to patients’ emotional wellbeing, including through providing entertainment. Patients who were able took part in recreational activities such as football and boxing. A weekly concert was held in the store tent.

Genuine friendships were also made. 3AGH’s Matron Grace Wilson and Staff Nurse Lucy Daw both write of visits from medical staff of other Australian hospitals. Likewise, Harry Gissing mentions catching the ferry from East Mudros to eat and drink with hospital staff. Personal letters and diaries also mention socialising in cafes and inns in Mudros, Castro and Therma.

Volunteer organisations

Volunteer organisations in Australia sent parcels abroad to bring some comfort and cheer to soldiers and other service personnel.

In July, a British Red Cross store opened in East Mudros. An Australian Red Cross depot operated from November. It provided 2ASH with deckchairs, games, mosquito netting and fly swats. It also presented a large rowboat to deliver supplies.

The Red Cross was not the only volunteer organisation operating on Lemnos. The YMCA was also present. It supplied a recreation tent and sold goods in a canteen.

‘We just love the R.X. & don’t think we could possibly get on without it. It is the loving Mother to us and the Army – we couldn’t exaggerate its value & appreciate it to the full. Yesterday I opened a box from Toowoomba, Queensland. There was useful comforts of all kinds – socks – mittens – mufflers etc. etc. The cigarettes tied up in the socks delighted the boys immensely.’

– Staff Nurse Anne Donnelly, letter, 10 Oct. 1915

By Christmas Day 1915, the Anzacs had withdrawn from Gallipoli. Many were regaining their strength and fortitude on Lemnos.

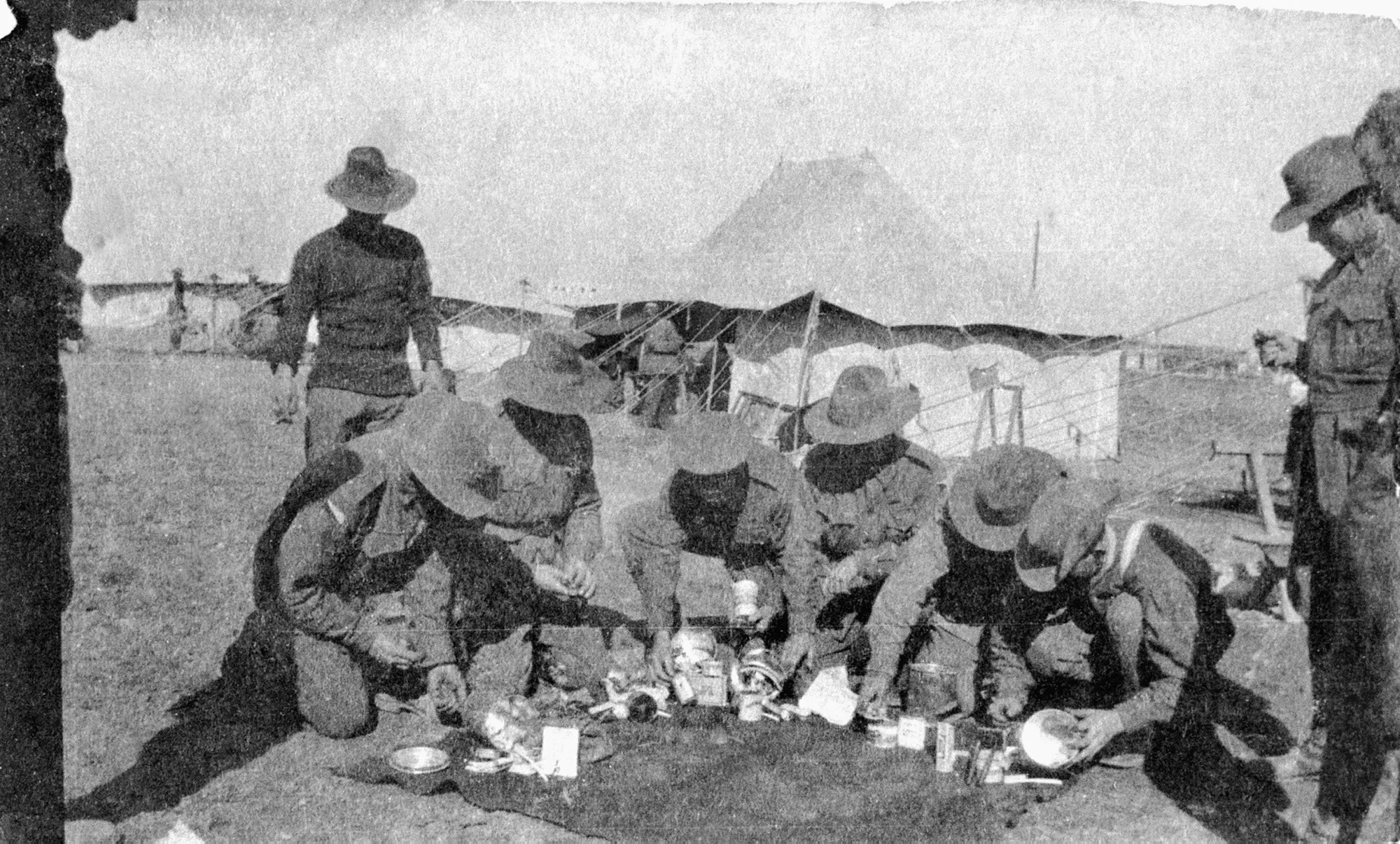

The Red Cross had helped distribute the Christmas billies that had been filled by citizens and volunteer organisations in Australia. They were filled with items such as knitted socks, writing paper, tinned fruit, cocoa, coffee, sauces, pickles and cigarettes – rare treats for those serving abroad.

The billies offered some excitement and sense of festivity. Importantly, they were also a tie to home.

The troops and other service personnel had seen such horrors over the previous months. Yet Staff Nurse Evelyn Davies could say that ‘Christmas on the island was happy’.

Interaction with locals

Lemnian merchants sold foods and wares from their boats on Mudros Harbour. Rear Admiral Wemyss wrote that they ‘Hawk[ed] every sort of commodity from onions to Turkish delight and Beecham’s Pills’. These were among the Allies’ first interactions with the local people.

In fact, trade was so brisk that authorities prevented Lemnians entering Sarpi Rest Camp to trade. Personnel movement was also restricted, and curfews implemented. Nevertheless, trade and tourism flourished in some villages. Civilians also came to the hospital precinct seeking and receiving care.

Exploring the island

Australians were attentive sightseers. The exoticism of ancient Mediterranean culture would have been fascinating. For some, it may also have resonated with tales of antiquity, Homer and Greek mythology.

Photographs and written accounts detail the landscape, villages and people. They demonstrate Australians’ interest in Lemnian culture and traditions.

Of Castro (now Myrina), Lance Corporal William Turnley noted that ‘quite a number of inhabitants could speak fair English’, which would have helped conversation.

‘The Island of Lemnos with its inhabitants is like a chapter out of ancient history. I think if we could have visited it two or three hundred years ago we would have found the people living the same kind of lives as today. The women may be often seen with their spinning jenny weaving their cotton. I purchased one as a curio.’

– Staff Nurse Caroline Allen, Bendigo Independent, 7 Mar. 1915

Relaxation

A visit to the mineral springs at Therma offered the prospect of a hot bath and a meal. It also meant the chance to relax in peaceful surroundings.

Given the limited freshwater supply on Lemnos – even worse on Gallipoli – a hot bath was a rare treat. Sister Olive Haynes had heard that ‘Helen of Troy used to bathe here’.

Australians appreciated meals served in the shade of the fig tree at the bathhouse cafe. Among the offerings were fruit, sardines, cheese and steak.

The journey to Therma from Sarpi Rest Camp was around 12 kilometres west along a rugged track. Some would walk; others travelled by donkey or on horseback. Some would also visit Castro, farther west, in the same journey.

‘We all had lunch. Omelette, cheese and biscuits and oranges – crowds of officers there, so we had to wait for the bath. It was beautiful. We had a bath, running hot water from the Spring all the time.’

– Sister Olive Haynes, quoted in We Are Here Too, p. 103

Just like home

Before the war, agrarian life on Lemnos was comparatively simple. Some Australians, likely farmers themselves, were curious about local practices. They noted wheat, barley and rye among the local crops.

Many visitors were also fascinated by Lemnos’s windmills. These made sense on an island that experienced howling winds.

My word, it was lovely to free from the hospital, and to be again out among farmers. Everything is old fashioned here. The farmer was ploughing with a thick piece of wood for a plough drawn by oxen. After he had ploughed he scattered the seed over the land with his hands.’

– Private Max Goyder, Express and Telegraph, 22 Dec. 1915

‘Just outside the village were several windmills, the sort one sees in pictures; a stone tower with the wheel coming out from near the top. Some had the sails up; others did not. All the corn is ground at these mills and wherever you go on the island there you will find the windmills.’

– Australian soldier, Laura Standard, 17 Sept. 1915

Spirituality

Most Australians who enlisted identified as Christian, but not all attended church regularly. The largest group identified as Church of England, followed by Roman Catholic and Presbyterian.

On Lemnos, Roman Catholic and Protestant services were conducted at Sarpi Rest Camp. Church parades on Sundays were also compulsory for all.

Yet some individuals sought to practise their religion independently. Sergeant Roy Rowe of 2ASH, for example, set aside time with a friend each night to pray and read a chapter of the Bible. Sister Betha McMillan wrote to her parents: ‘I have the Psalms & St John in Modern Readers Bible. I got them at Mudres – been great comfort to me.’

The Greek Orthodox Church was the religion of Greek Lemnians. Many Australians visited their churches, including Evangelismos tis Theotokou in East Mudros. The rituals, decorated interiors and services all interested them.

Private Hastings wrote of the church bell that ‘peals its peaceful invitation to devotion and worship’. Private Weymouth recalled a funeral for a member of the 9th Battalion. He had died in his tent before the Gallipoli landings. With no Roman Catholic priest on Lemnos, the Greek Catholic priest had officiated.

Visitor fascination also had a negative impact on the churches and community. There were reports of several thefts, including of an altar stone, lamps and holy relics. The vice of souveniring appeared alive and well. Senior leaders condemned such conduct and issued serious warnings to troops.